BLOOMING AT THE END OF THE WORLD: KEITA MIYAZAKI

March 14 - April 27 , 2024

Imagine a world of ruins in which a flower takes root. It blooms, it thrives. It is sent with a letter to declare life after an end. Its sudden, slow growth is a beginning, a new present emerging from the transformation of debris. Now time has branched out, split itself, and created a place of renewal. In this after, the flowers move imperceptibly, they multiply. Such a future is an outcome of disaster, its beauty cuts through an era of mourning.

For long, modernity promised an uninterrupted future. A time of automobiles speeding across smooth concrete, a time of metal striking metal in factories. A time of prosperity. To think about the future today is to doubt its existence. In this present of never-ending horror, the future appears foreclosed. Without any exit from devastation and exhaustion, we are bereft of modernity’s pledge of a brighter, better, faster time. Instead, the apocalypse is here, no longer a distant threat. It has been revealed manifold, and for long to stewards of the lands, whose oppression and erasure was necessary for colonisation and extraction, for the idea of infinite development.

We are now running out of time, overcome by waves of disease, watching storms on the horizon, eyes burning and lungs filled with particles that leave irreparable shadows.

If we were to think of a symbol of the belief in this future past, its ambitions could be encapsulated in the body and the movement of a vehicle. Over a century ago, poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti exalted the ability of the car to cut through time in his Futurist Manifesto: “We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched with a new form of beauty, the beauty of speed. A race-automobile adorned with great pipes like serpents with explosive breath… a race-automobile which seems to rush over exploding powder…” Marinetti’s doomed fascination for violence led him to draw an accurate parallel between the machine and the larger project of progress, all in celebration. The dream of mastery that he described fuelled the circulation of capital between economies. It was a result of the brutal ideological separation between nature and culture. Of this unending appetite for acceleration, philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi writes: “The myth of speed sustained the whole edifice of modernity’s imaginary, and the reality of speed played a crucial role in the history of capital, whose development is based on the acceleration of labor time.

There are the images that the car evokes, and there is the reality of its functioning—of a body built from metals, of engines running on oil, both taken out of the heart of the Earth. These materials contain time so vast we cannot envision it. They were part of a subterranean cemetery of animals and plants that lived long before us. Their continued extraction has led to planetary exhaustion, exhaustion of the human body and psyche, and the end of many living beings—all distributed in inequitable patterns across places and communities. Thus one way to image the end of the era of the speed, that is the era of catastrophe, is to halt the movement of the automobile, to agree to watch it decay over time, to leave it stationary. Since capital always find a way to circumvent its arrest, this future can only be the result of disaster. We have already seen abandoned towns with rows after rows of decaying cars, grass growing tall around them, yet the rest of the world carries on.

In 2011, the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami led to the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan. At the time, it seemed to have demarcated a point of termination. Artist Keita Miyazaki remembers the widespread fear of contamination, the abandonment of homes, and debris piling up. From Tokyo, Miyazaki watched as entire towns were swept away, as mushroom clouds rose into the sky yet again, and radiation began to leak into the surroundings and beyond. Political theorist Sabu Kohso has described Fukushima as “a catastrophe without end” not only because containment is more or less impossible but also because the possibility of such an accident itself is indicative of the organisation of power in a capitalist world order. Although it may have seemed like Fukushima would mark an end, it did not, and the march of the nuclear nation-state continued. Fukushima in Kohso’s understanding is not an isolated incident but a metaphor for cycle after cycle of disaster and its wilful perpetuation across the globe.

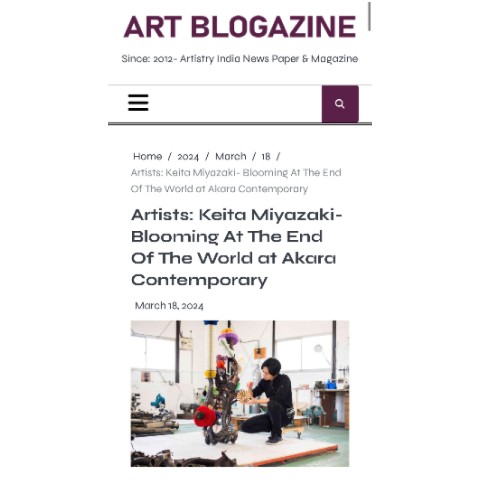

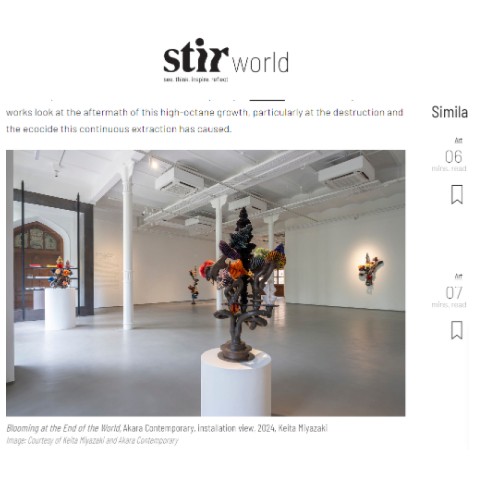

For Miyazaki, some of the most striking pictures that emerged after Fukushima were those of all kinds of objects, left standing or seen floating out to sea. It altered his understanding of material and artistic production. Among the refuse, Miyazaki was particularly drawn to abandoned cars because they were symbolic of Japan’s automotive industry that drove the country’s economy forward after the devastation of the Second World War — an industry that, defying logic, was possible in part because of energy generated through nuclear reactors. With sensitivities nurtured by his training in craft metal-casting, Miyazaki began collecting car parts, seeking a mode of expression relating to the collapse that he had witnessed. Miyazaki thus began creating assemblages that seem to have an existence outside the patterns of wreckage and reconstruction, objects located in the landscape after the apocalypse. Made from the body of the dismantled and obsolete machine, Miyazaki’s sculptures are botanical, with the suggestion of slow movement. They indicate growth and renewal, hybridity and glitching. Their presence rearranges the order of things and disrupts the notion of the linear motion of labour. They are flowers blooming at the end of the world.

In these sculptures, parts from automobiles and handmade paper constructions are assembled in a way that each of these becomes something other than itself. The exhaust pipes are now branches on which vivid blooms thrive, appearing robust and astonishing. It is as if we have travelled away from an environment of function into an enclave of probabilities, where the pipe no longer billows smoke into the air, filling lungs with particulate matter, nor does the metal body to which it would have been attached move capital forward. The skeleton of the car is now arrested, and scraps of it have become relics. In this new form, they make us consider the spectre of planetary catastrophe, death and extinction, and the subsequent alteration in the flow of time.

The materials that Miyazaki uses in his sculptures are not only industrial products but contain within their making knowledge collected over long durations. The paper parts are usually assembled in the form of the honeycomb, a pattern found in hives and bones. The tenacity of this hexagonal arrangement was understood by bees long before it was put to industrial use to make engine parts such as radiators, but it also serves as a structure in decorative ornaments, which is where Miyazaki re-encountered it. These uncanny echoes between animal life and mechanical objects lend the paper forms that themselves appear like flowers shifting meanings.

As for metal, Miyazaki has a particular expertise on the subject of its moulding. He holds a PhD in craft metal-casting undertaken in Japan, where the course is intended as much for making new objects as for restoring the old. The oldest known example of metal casting in the world is supposed to be a bronze frog produced in Mesopotamia dated to 3200 BCE, where the animal was treated as a symbol of fertility. The technology to produce alloys and pour the liquid into moulds to produce art, currency, tools and weapons developed at vastly different moments in different locations. Present inventors build on the past so in a sense we can draw a line from the frog to the Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro, from a coin hidden in the pocket of a sailor to the cannon mounted on the ship, from the letterpress that was used to spread news to the vehicle that nourished the idea of individual autonomy. This seamlessness is seductive and beguiling, much like the beauty of ruins. However, it does allow a bewildering vision of material and form reconsidered through the composition of Miyazaki’s sculptures. For the last few years, some of Miyazaki’s sculptures also feature their own handcrafted metallic parts, in a gesture that allows histories to collide against each other.

Looking at Miyazaki’s sculptures leads nevertheless to a rather simple question: how do we slow down yet flourish? Perhaps, we might want to abandon the idea of a singular future altogether by taking recourse in plurality. What if this plural time is not an escape but a site where one can confront, halt, or even suspend the churning of the present? Where would we grow if we began at the end?

Zeenat Nagree

Independent Writer & Curator

Independent Writer & Curator